‘Boundaries in the Making:’ Concepts for a New Housing Community in Belfast

In 2022, Brown and Storey Architects participated in the City of the Future Competition in Belfast, Northern Ireland, a call for architecture and urban design ideas to build an inclusive and sustainable community on the 25-acre former Mackie’s site. Brown and Storey’s shortlisted competition entry is below.

Summary

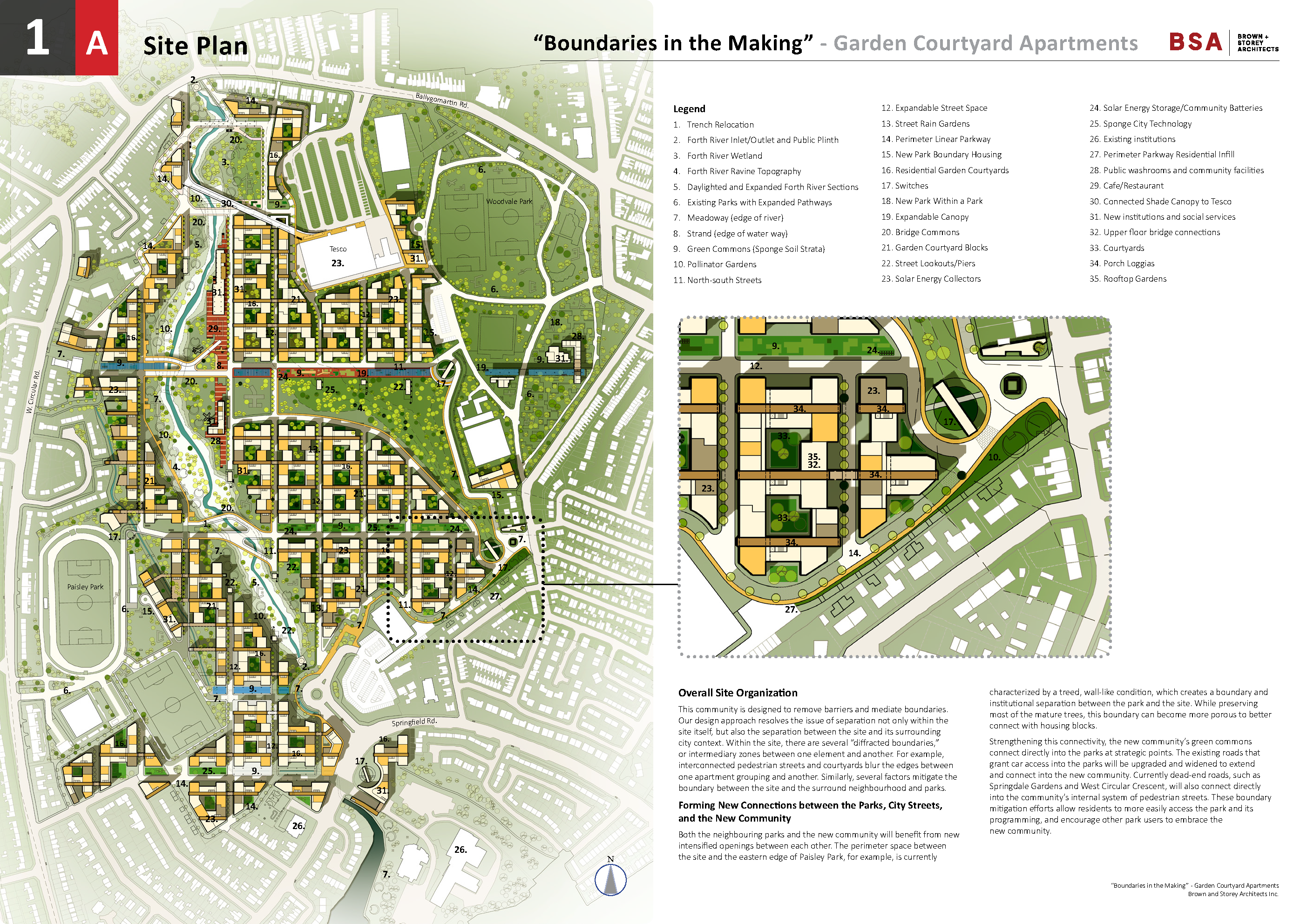

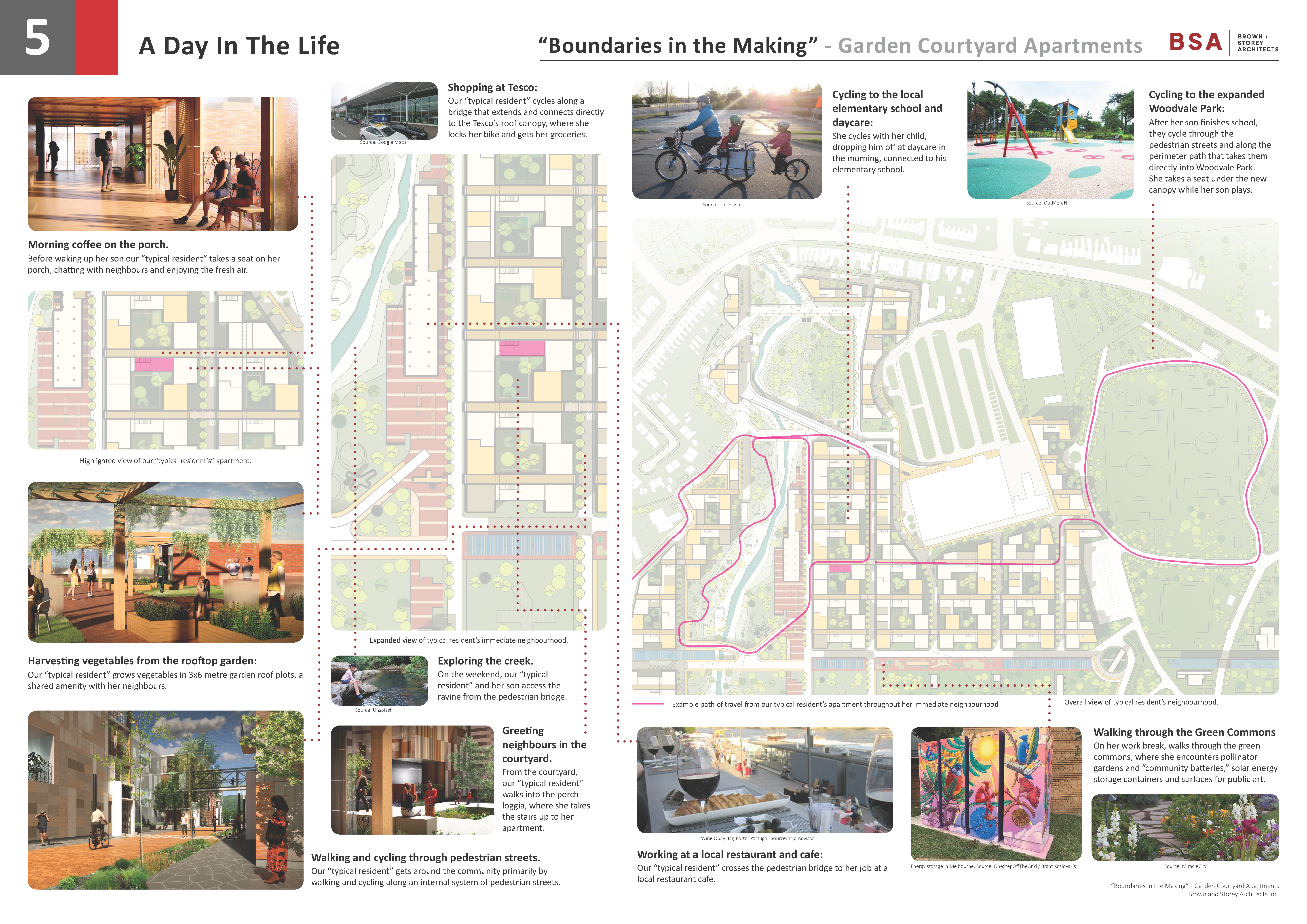

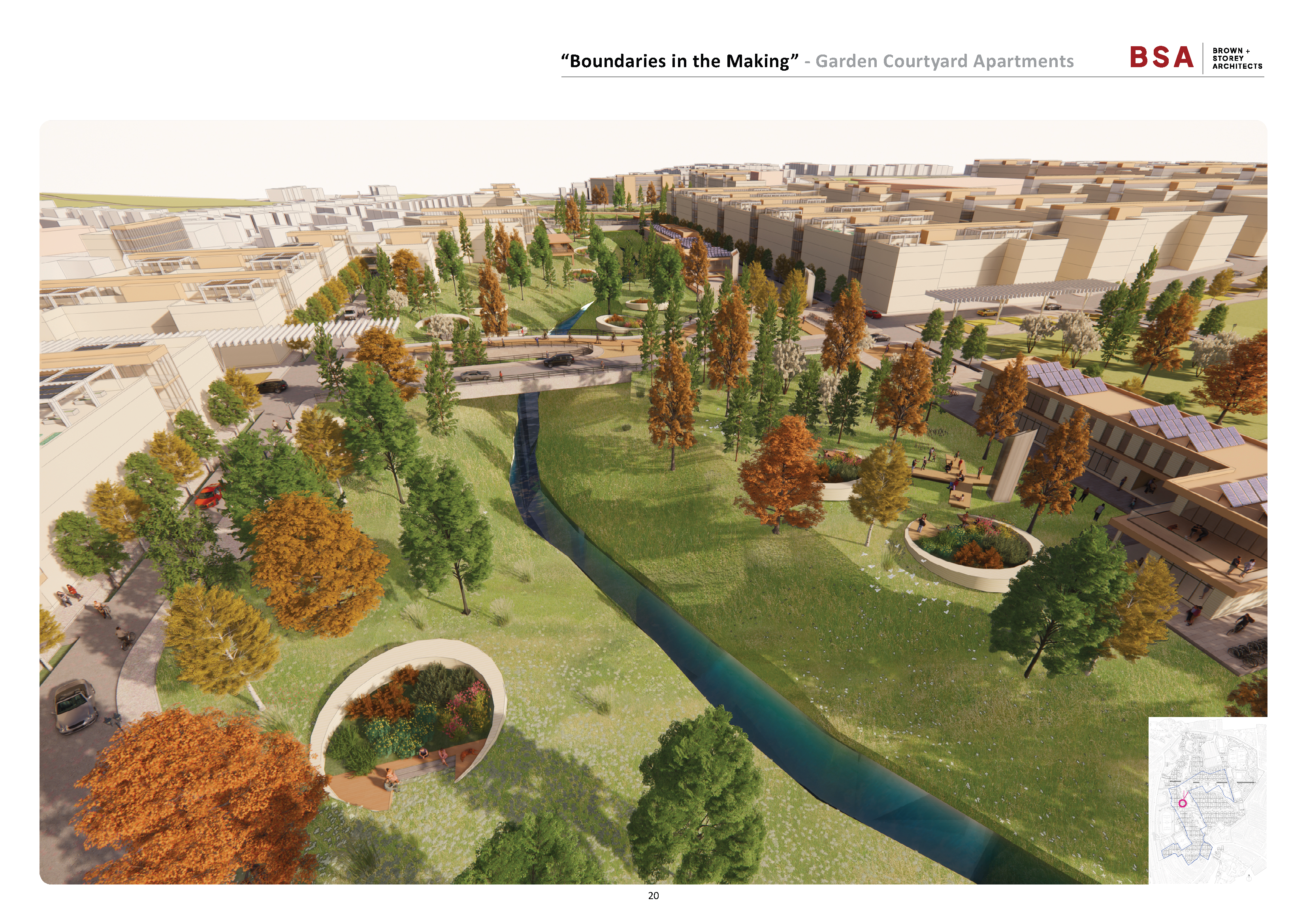

The daylighting of the Forth River and its existing topography establishes and reasserts the site’s founding landform and identity. Within this site are numerous new streets and green commons that organize the many Garden Courtyard blocks around the natural landform. We have intentionally seen these car-free streets and green commons as open “boundaries in the making.”

The streets are configured to allow for expansion at their edges. All the streets are different and simultaneously pedestrian and multi-modal, while allowing for service vehicles. The streets are expandable and open multiplicities that have environmental functions and renewable energy capacities.

In a similar manner, the numerous wide public commons organize the larger site into strips, interacting with the streets and the new emergent landscape. The green commons are also open and not overly delineated. They carry storm water with their “Sponge City” technology, and are the locales for renewable energy storage facilities or “community batteries” that reference various scaled garden courtyard groupings.

The park commons, the streets and natural topography set relations of elements and describe various scalable and non-scalable relations between the residential environments. The streets are non-scalable; some streets are more connected than others. The streets that encounter the founding landform become piers, lookouts and environmental stations.

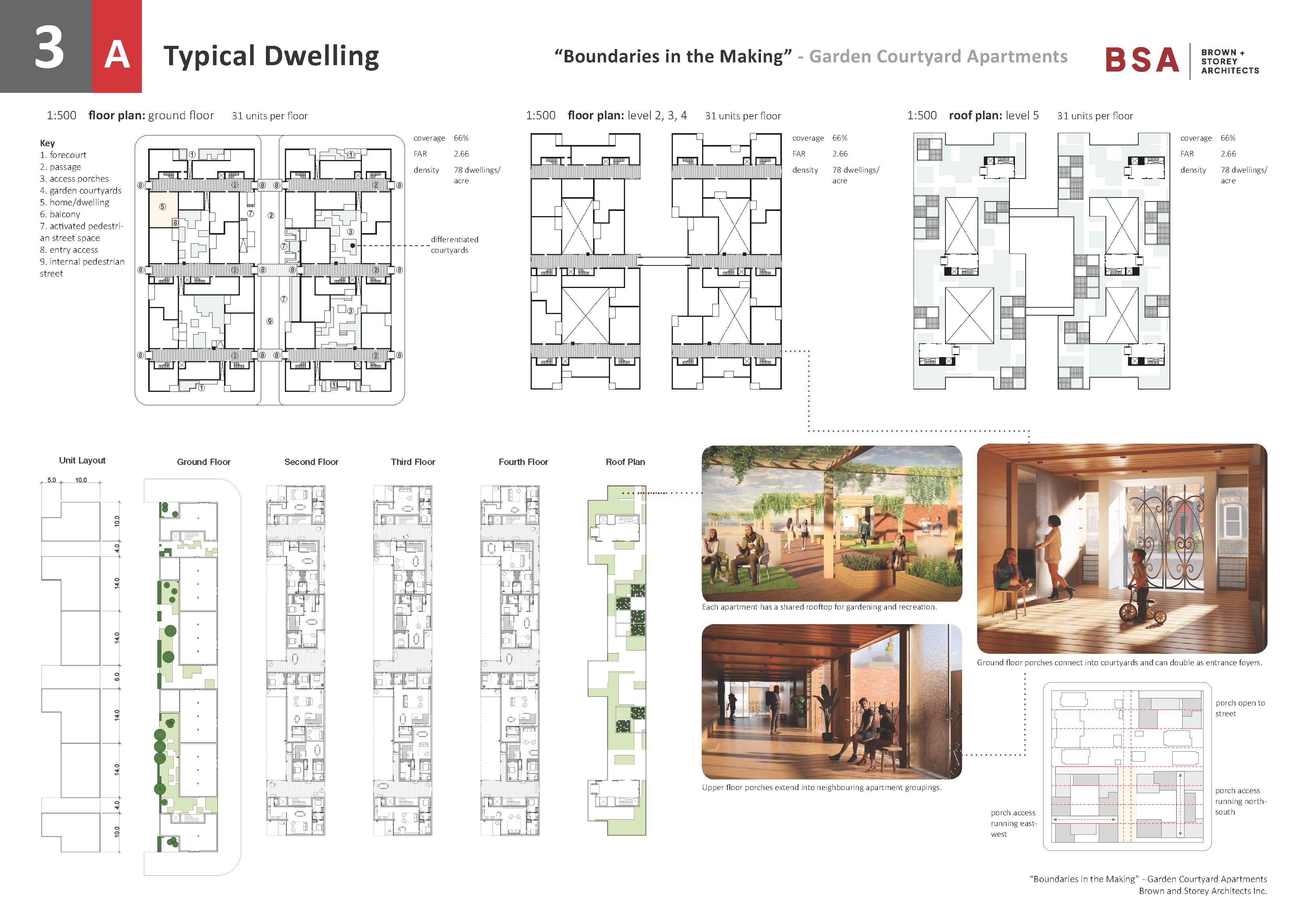

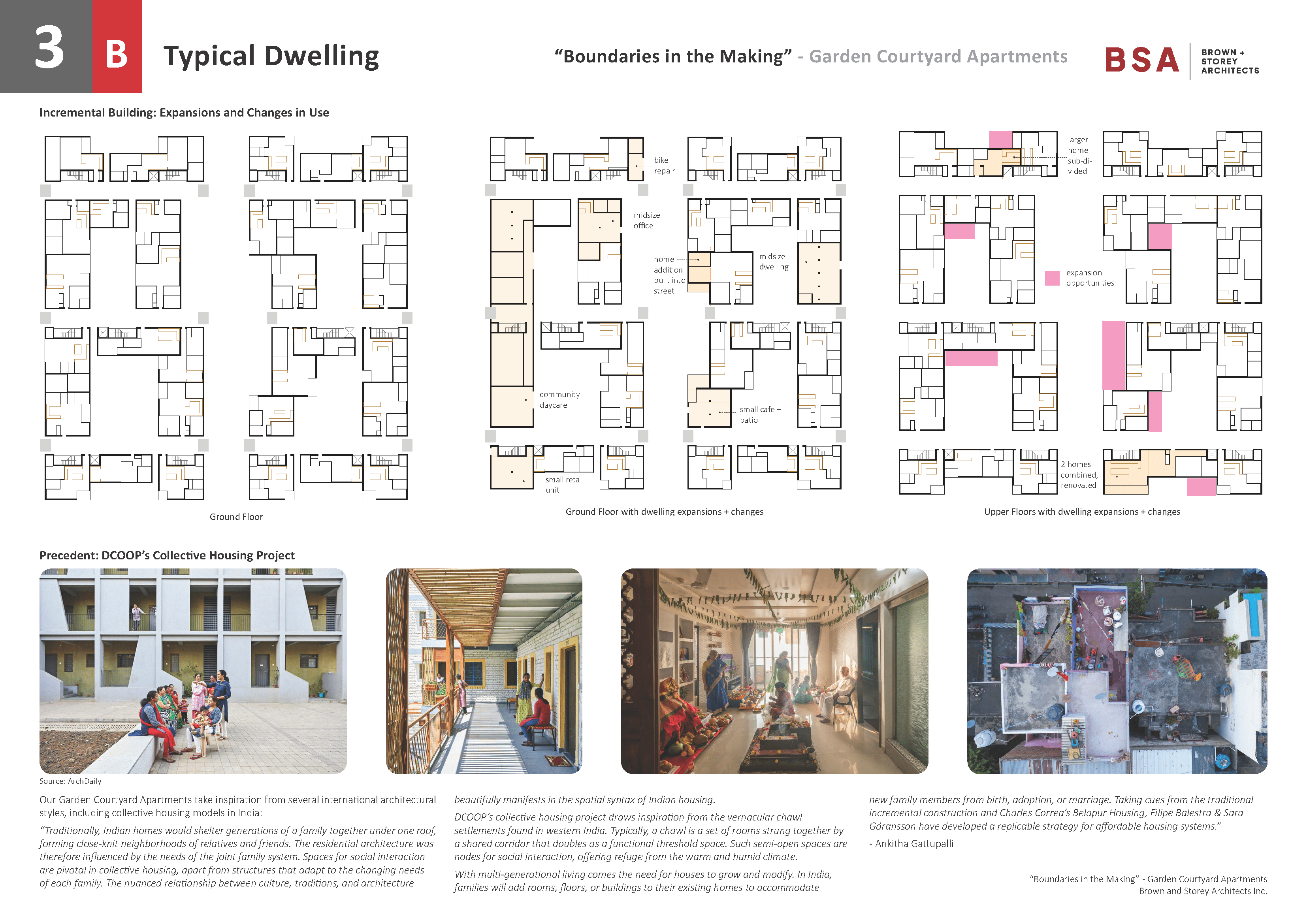

Everything expands outward from the residential garden courtyard apartments, yet they have a defined spatial configuration. The numerous courtyards are quantifiably and qualitatively different, subject to the households living there, and create instant community. They form various scaled blocks, some open-ended, others limited in extension.

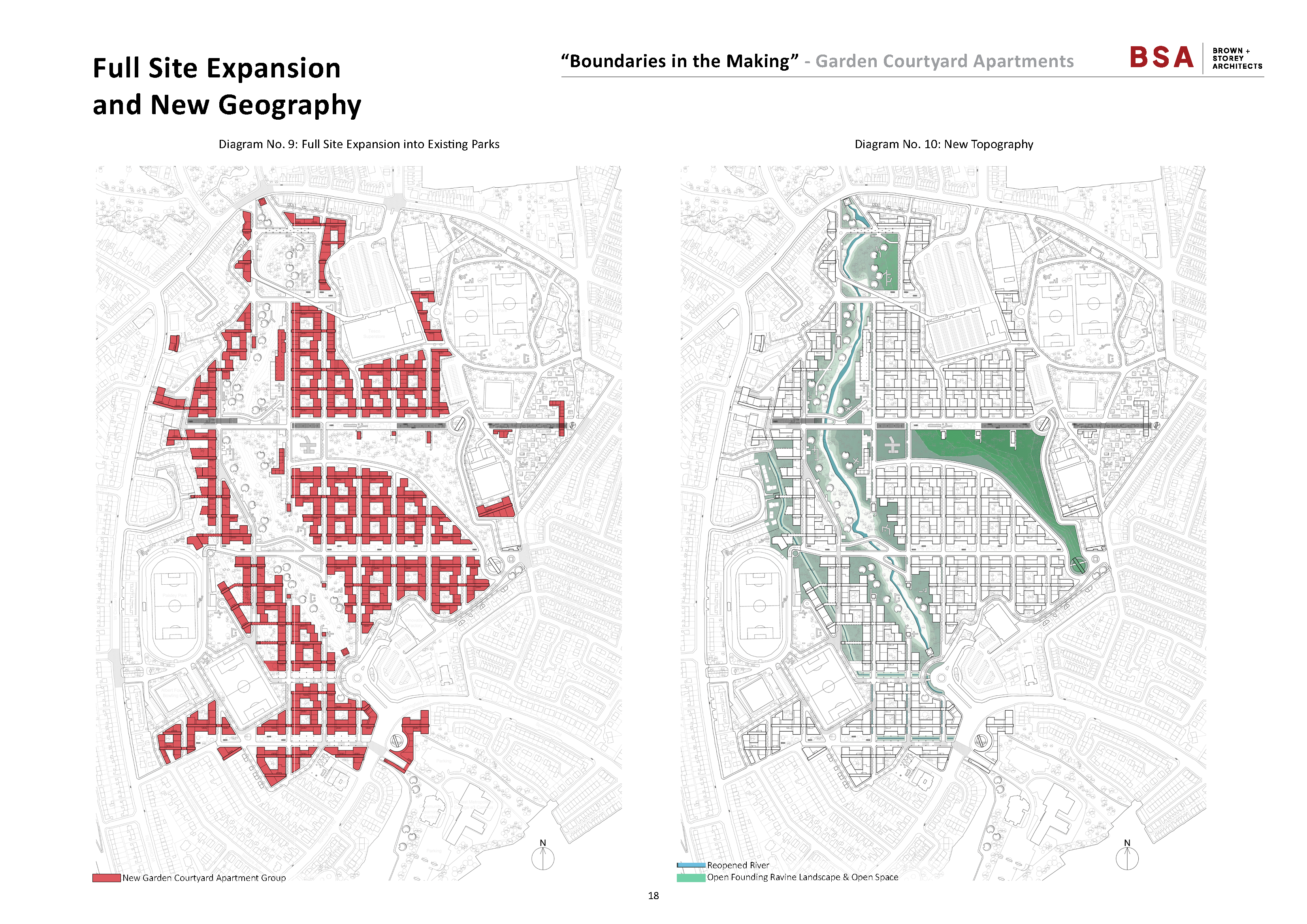

The two large adjacent city parks currently exist as separate destinations that mostly require car access. This suburban separability has boundaries that we have intentionally opened up. We have located residential housing at their boundaries, created new “switches” or public linkages to them, and expanded their pathways to extend to the new community’s street infrastructure.

In particular, the central green commons extend into both parks and establish a new more democratic, scaled set of park spaces and amenities in a new matrix. A new, expandable shade canopy connects the neighbourhood with the park, and organizes a public building with restrooms and new connections to the surrounding city streets.

The new Mackie’s site neighbourhood and environments present a challenge in not pre-naming the new urban spaces, but letting them evolve and find relationships between the households and potential residents. Rather than a keyed site plan, we have generated categories that do not limit the qualitative nature of elements.

Categories of Relations of Elements:

The site includes:

- 45 Garden Courtyard interconnected full and fragmented blocks

- 107 Garden Courtyard groupings

- With each grouping, there’s a minimum of 5 dwellings per floor x 3 floors = 15 dwellings.

- 15×107 = 1,605 dwellings total

- With each grouping, there could be 9 dwellings per grouping per floor x 3 = 27 dwellings

- 27×107 = 2,247 dwellings total

- As the variants increase, with smaller dwellings, the total number of dwellings increases

- With each grouping, there’s a minimum of 5 dwellings per floor x 3 floors = 15 dwellings.

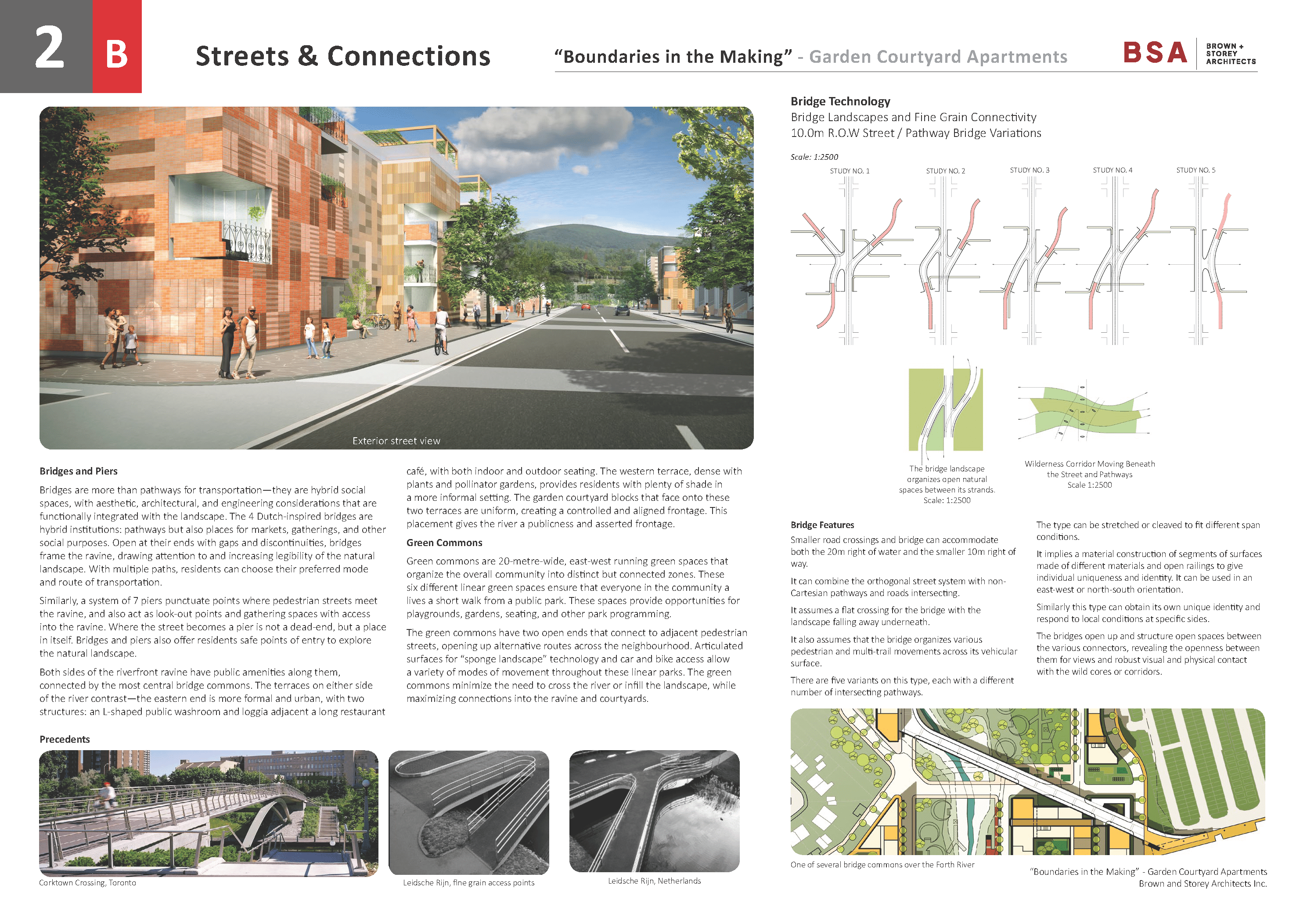

- 4 public/pedestrian access bridges / bridge commons

- A pedestrian and cycling network organization for the site

- 3 new connections to the adjacent city parks and their corresponding building sitings

- A new covered linkage to the existing large Tesco store

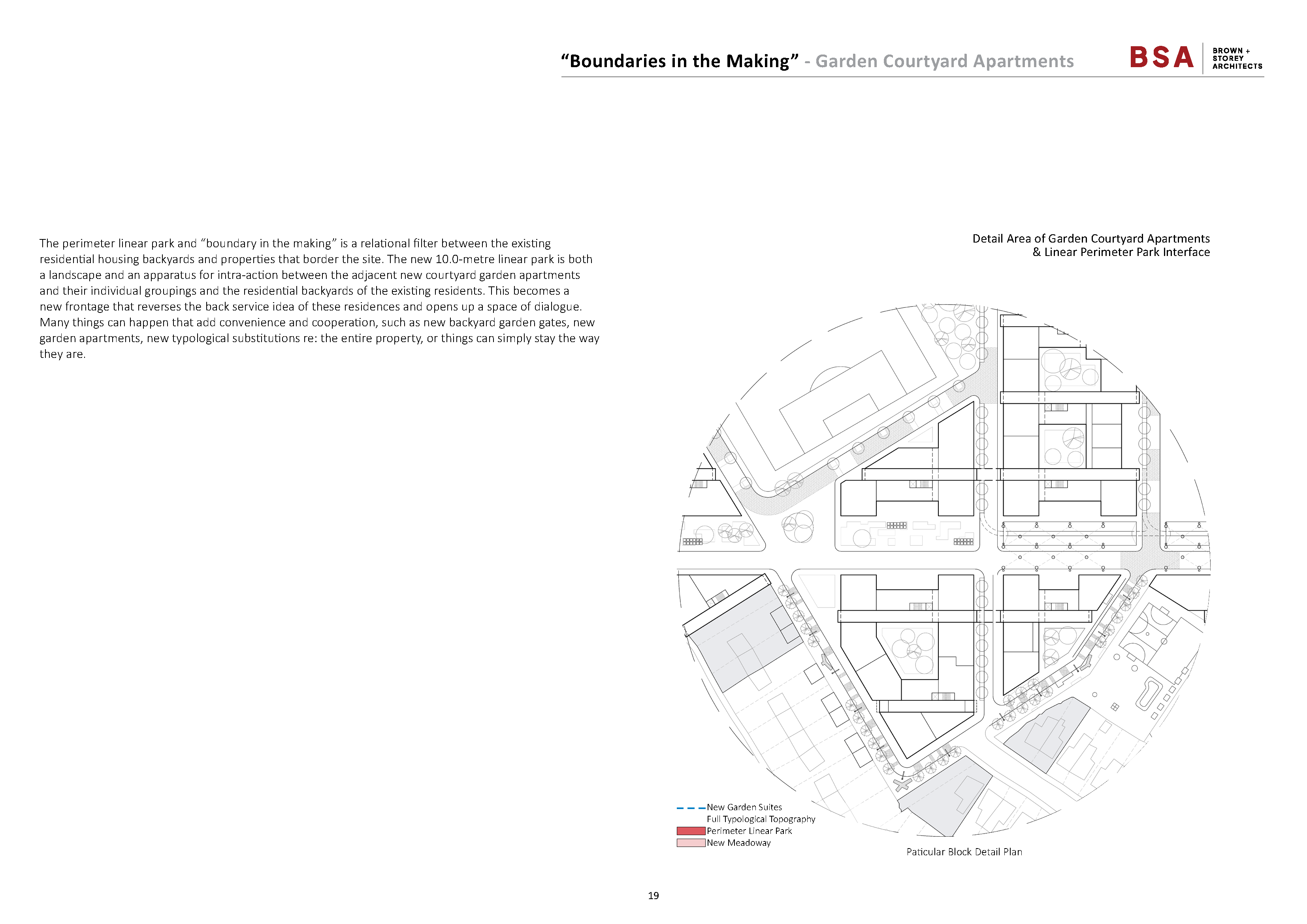

- A continuous encircling 10.0 m perimeter linkage and linear park around the site

- New residential buildings at the larger site perimeter

- Pollinator gardens and green commons through the site

Competition Panels

Post-Competition Work

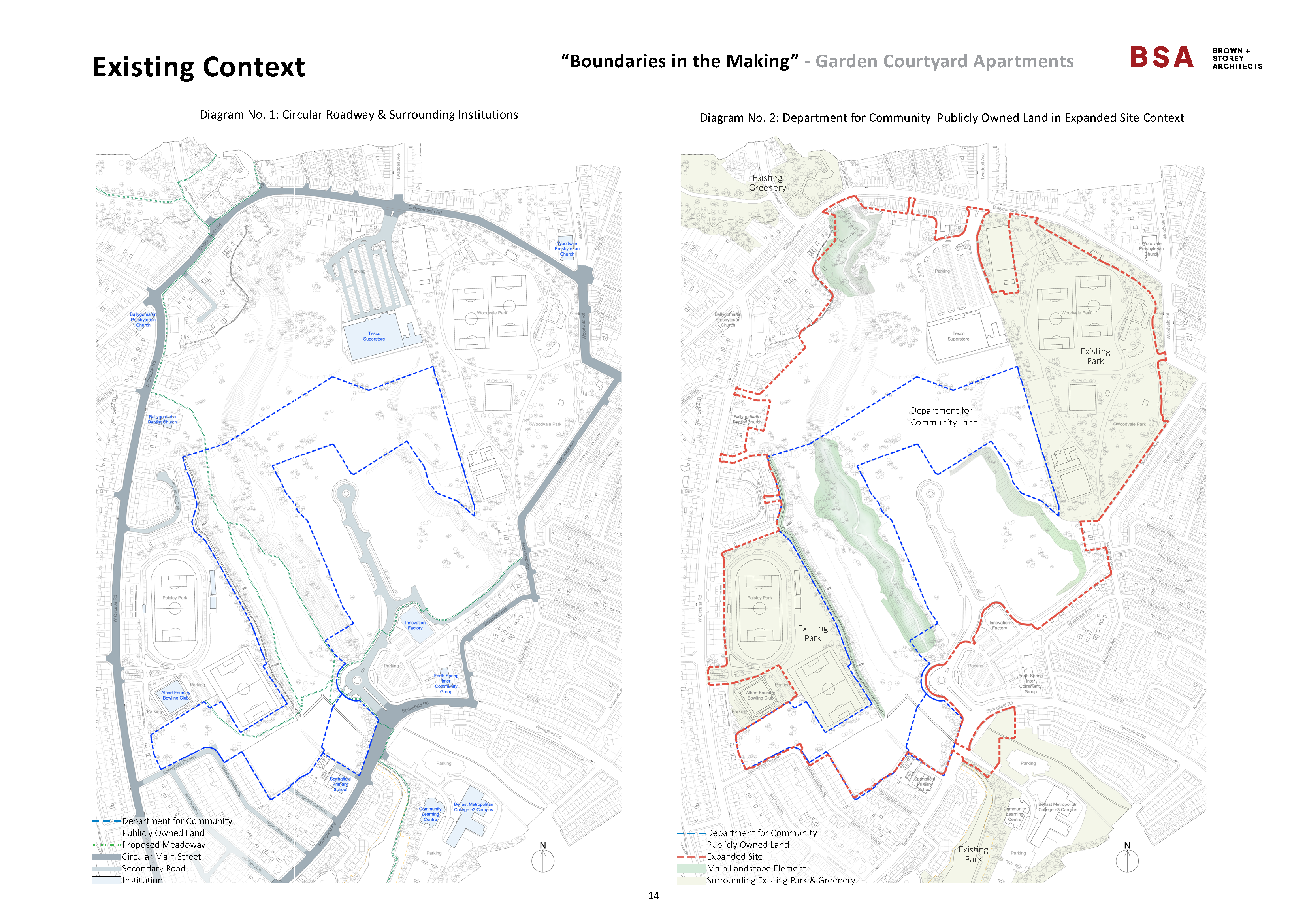

The Existing Site and its Relations to its Outside Boundaries

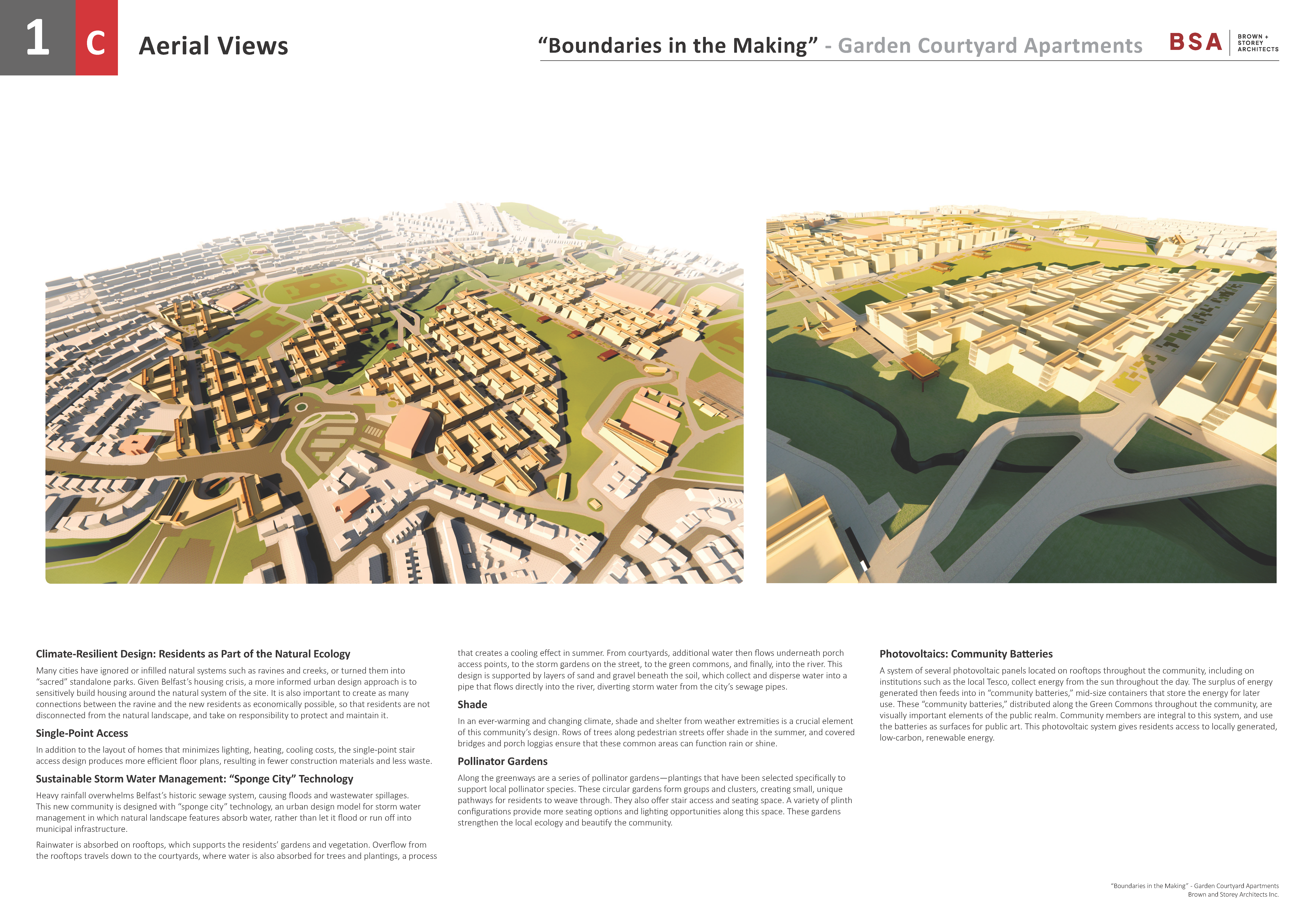

The former industrial Mackie’s site contains the Forth River, which runs partially above ground with its end points undergrounded. The Mackie’s site is a remnant ravine with no streets or meaningful public spaces within it. The soil conditions are likely toxic, and large vacant space is mostly invisible from the streets that surround it. Three large parks form close boundaries to the site. These parks are suburban, Victorian-style, drive-to locations, catering to the single family neighbourhood that surrounds it. Other large suburban entities such as the Tesco supermarket and the Innovation Centre form an un-composed milieu of locations with a scattering of small schools, churches and other institutions. The site is a mix of different ownerships that have no explicit overall planning idea for a future direction.

A new beginning is required to reimagine the site for new housing possibilities. The inner boundary of the site includes a multiplicity of edges, including residential backyards and park boundaries that back onto the site with no points of access or circulation systems. There are also several surrounding streets that dead-end at the border of the site. There are very few “openings” that could connect the imagined housing entity to the surrounding city.

The site requires major interventions to reverse some of these larger geographical and topological and post-industrial constraints. Our approach, after a number of false starts, is to look at the maximum potentials of the larger ownership assemblies was the place to start, as well the notion of a restriction-free site with no zoning or pre-determined ideas.

Integrating the Site with the City

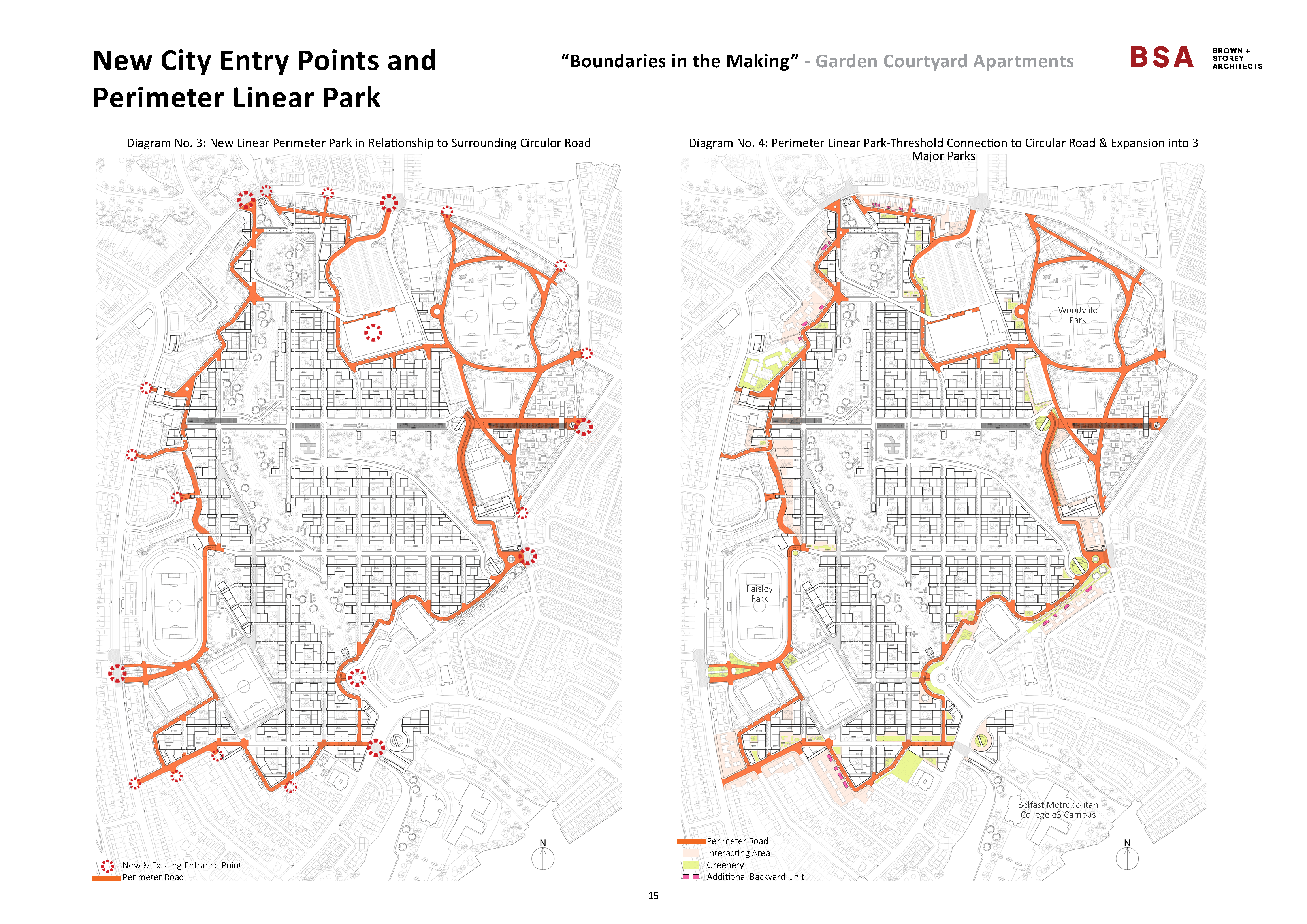

Given the internalized nature of site and the back conditions along its perimeter, how do we establish a system of connectivity between the site and the rest of the city? This site requires reciprocal relationships with these larger sites. The social issues plaguing the parks are well known and require a solution that changes their very constitution and separated spatial framework.

A 10-metre linear perimeter park around the site would break down the barriers between “inside” and outside,” forming a new network. The new neighbourhood, existing homes, and institutions can then form new relationships with the site and its garden courtyard blocks, streets, and Green Commons. The surrounding parks and their outer boundaries that contact the inner site are activated and brought into a more operational relationship to the site. Where possible these “lost boundaries” are given a new role and importance.

The boundaries between the site and the city are currently closed, with parking spaces, fences, or lines of buffer trees creating separations. The interchange along these boundaries introduces “switches,” points of access which in some cases accommodate new housing sites. By consolidating various parking locations, new space is gained for more housing.

When added to the park, the housing and new residents significantly transform the isolated, one-dimensional definition of the parks. The new positioned residential structures bring not only more life and vitality to the park, but also introduce a historical precedent that could contribute to the economic upkeep of the park. This newly intensified publicness and more “eyes” on the park may also help reduce the social problems that have plagued the space.

The 10-metre perimeter is not just a multi-use path, it’s a new growth zone for nearby residential landowners to take part in a new operational expansion. This space of expansion is a “cut” that initiates the reorganization of the site with an inclusionary “boundary in the making.” Home owners can expand their rear lot lines, create new entrances, garden suites, and choose to keep their backyards open or closed. This embryonic space creates new frontages that can absorb the site’s streets, Green Commons, and other infrastructures of the new neighbourhood, preventing discontinuities. This catalytic, porous park space is multi-modal—it accommodates cyclists, pedestrians, park users, and service vehicles, and offers alternatives to driving around peripheral roads to get around the site.

The perimeter park is kind of forest that gets punctuated at various locations, meeting wider garden locations, small parks, and intersecting streets and commons. It is important to emphasize that the linear park shares thresholds with the garden courtyard apartments and their connective elements. Apartments’ entrance loggias punctuate the linear park and are responsive in a changing series of profiles, each governed by the siting and positioning of the garden courtyard groupings. While simultaneously creating convenience of access and mobility, the surrounding park echoes the exterior circular roads of the outer site, although these new roads are pedestrian-oriented.

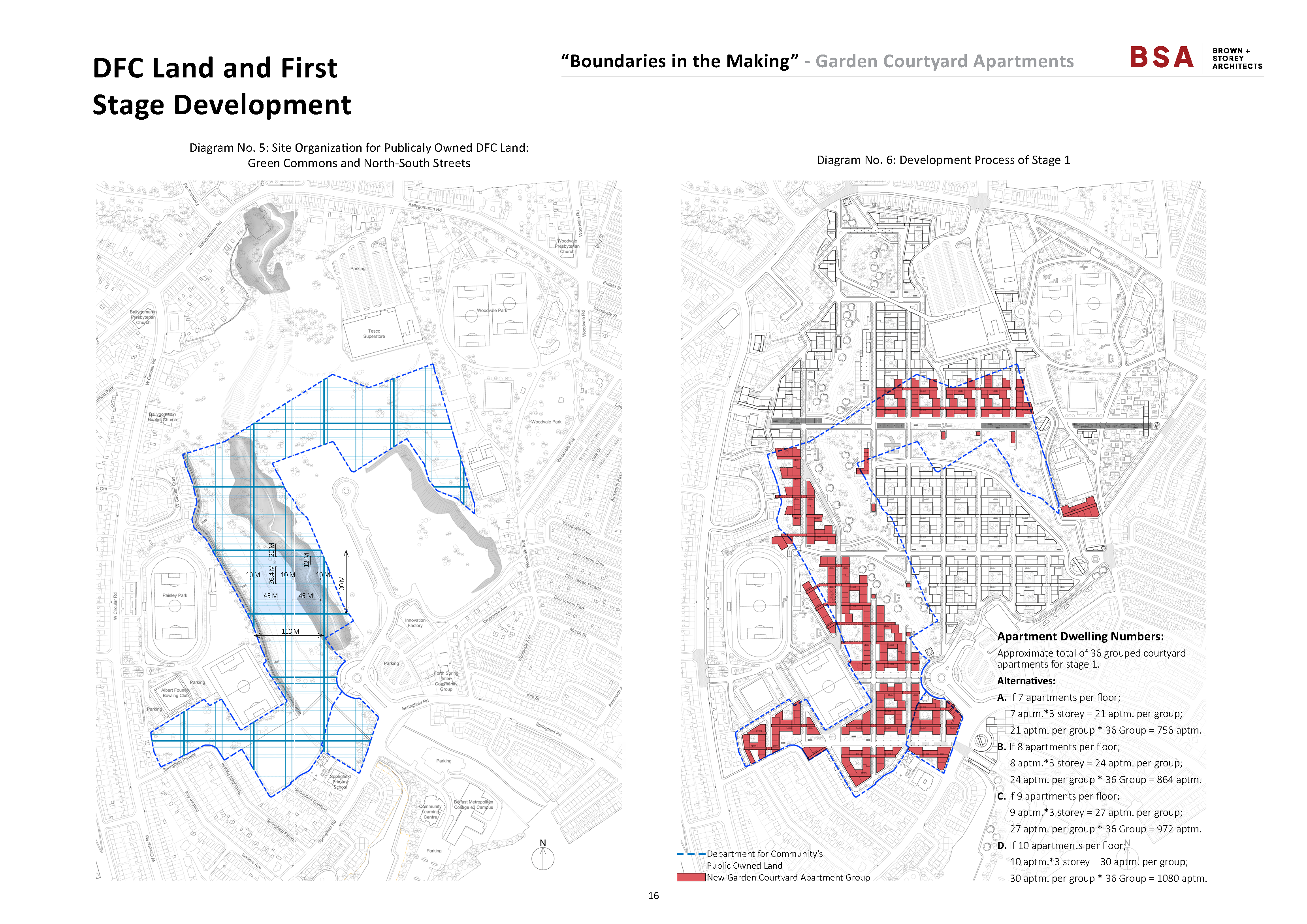

Building a Maxima Residential Garden Courtyard Housing Template

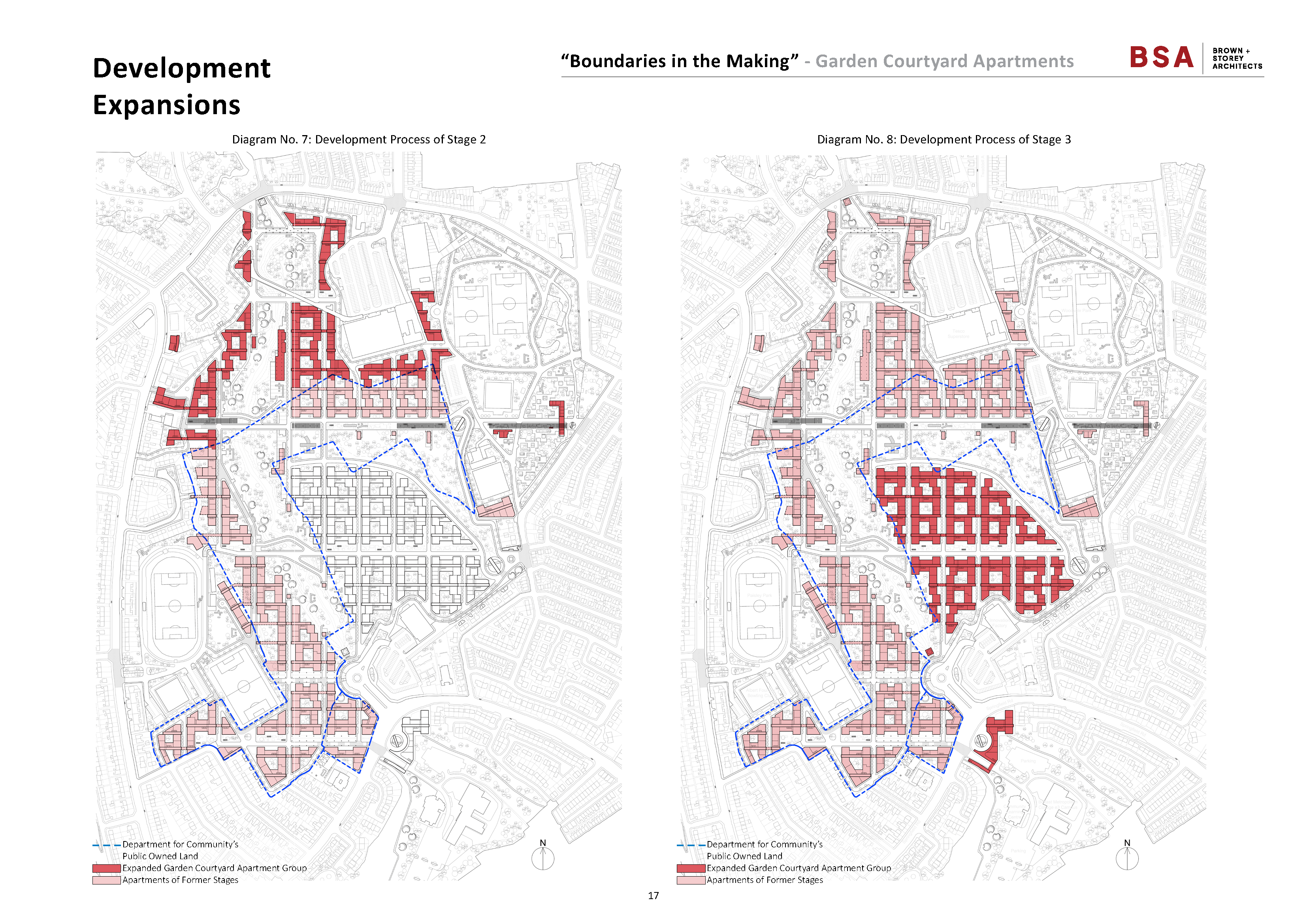

Building tightly around the topographical features, the garden courtyard blocks and superblocks use as much area as functionally possible on the site to maximize housing availability. To further increase the number of dwellings available, the buildings can be increased from three storeys to four. The residential garden courtyard typologies could easily accommodate an extra floor without jeopardizing the liveability of the apartments. When considered on the larger scale of the site, the Green Commons and edges of the Forth River have adequate capacity to accommodate a wealth of different users.

Superblock Communities

The hierarchical order of housing in the “Boundaries in the Making” project on the Mackie’s site can be organized into three distinct categories: individual garden courtyard apartments, blocks of garden courtyard apartments, and finally, “superblocks,” or larger groupings of garden courtyard blocks. The concept of the superblock is the result of integrating the garden courtyard apartments with the topographical features of the site as well as the bridges that unify the site.

Just as the individual garden courtyards and blocks are interconnected, so are the superblocks. The internal linkages between courtyards, porches, and streets give the garden courtyard blocks a distinct identity and a safe internal environ. The superblock, a “community within a community,” expands on this collective environment. With vehicles primarily using roads around the perimeter of the superblocks, the internal streets within them are freed up for pedestrians and cyclists.

The overall organization of the apartments are highly responsive to the existing geography and spatial allocations of the founding ravine. The large superblock configurations establish a frontage along their boundaries, creating distances between them that correspond to the site’s founding natural landforms.

Social Geographic Organizational System

The relationship between the various scales of elements is not simply a matter of geometric nesting, but an intra-active topological matter. The connectivity between these ranges of elements requires an analysis of the sort of connecting phenomenon at different scales. The transition through the range of scales avoids the social exclusivity often associated with geometrical hierarchies. These places are made through one another, through connectivity and agential intra-action.

Politics of Open Possibilities

Concepts such as proximity, location, distance and scale do not necessarily have to depend on an intrinsic metric. These concepts should be understood in terms of boundaries, connectivity, internality and externality. The shifting entanglement of relations is not defined by the politics of location or the container model of space as fixed entities, but the politics of open possibilities.

Notions such as location are opened up by spaces of agency in which the dynamic interplay of indeterminacy and determinacy reconfigure the possibilities and impossibilities of becoming. This means that indeterminacy, contingency, and ambiguities co-exist without the need for the usual spatial definitions and “fixity.” Jumping scales and boundary transgressions break down “dominant” hierarchies in favour of “in-the-making” thresholds.

The Threshold Paradigm and the Green Commons

The threshold metaphor offers a counter-example to the dominant concept of the “enclave” city. Rather than perpetuate an image of separable enclosures, the challenge is to create spaces that inventively disrupt the dominant taxonomies of exclusive spaces and clear lifestyle distinctions. Thresholds explicitly symbolize the potentiality of sharing by establishing intermediary areas by opening the inside to the outside. The creation of common spaces involves practices of transition that build bridges between people with different political, cultural or religious backgrounds. Spaces as “thresholds” become active catalysts in the processes of re-appropriation of the city as commons “in the making.”

The Green Commons traverse the site in an east-west orientation, connecting across the Forth River via pedestrian bridges and extending into the surrounding city parks. A ramp or “switch” allows the Commons to adjust to variations in the site’s grade. The Commons are combination areas that could take on a range of different social or agricultural functions, from orchards to collective community gardens. These open areas can be home to climatic modifiers such as shade canopies, lines of trees, as well as locations for photovoltaic community batteries. True to the idea of Commons as shared space, the commons interact with the adjacent streets and garden courtyard apartment groupings.

Most fundamentally, the Green Commons are “sponge” landscapes that absorb, store, and transport water to the Forth River. Storm water falls from garden courtyard roof terraces, to the courtyards, under loggias, into the pedestrian streets with their storm gardens, and finally to the Green Commons with their specified soil stratifications. Above ground, the Commons provide space for public events and daily outdoor use with an openness and spatial integration with the natural geography of the site and the large parks—they are catalysts in the making.

Patch Dynamics

The three, patch-like superblocks in the “Boundaries in the Making” project exist within a perimeter of existing roads and houses. Although the founding site has no existing road structure to build upon, the three superblock patches extend into the surrounding context where possible, forming connections with the existing network of streets and parks. Woodvale and Paisley parks constitute a large area of the perimeter around the site, reducing opportunities to connect the site into the surrounding streets. However, the scale and autonomy of the large patchwork of superblocks creates the necessary scale to overcome this separation.

The Pollinator Garden Pathways

Pollinator gardens flank both sides of the Forth River. Various arrangements of pollinator-specific plantings are placed in elevated, circular taluses with a sloped orientation and a compact set of steps allowing access to the surface. These taluses are dispersed in directional alignment along frayed, varying edges of the meadoway, forming an archipelago-like garden pathway. The pollinator gardens are catered to the behaviours of bees and other pollinators, who make frequent stops along linear paths. Similarly, the pollinator gardens invite pedestrians to weave their way through footpaths, or take a seat on the raised surface.

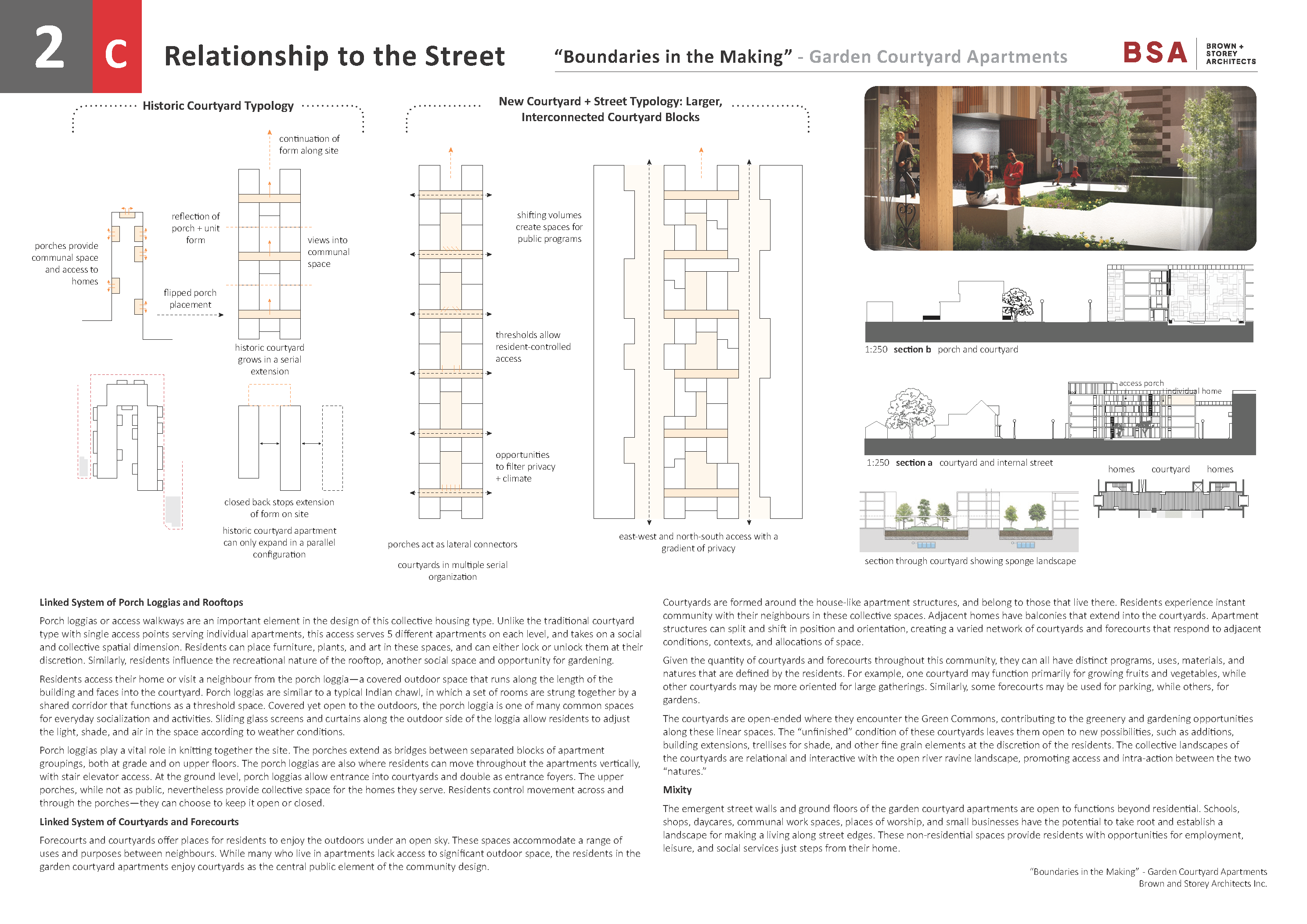

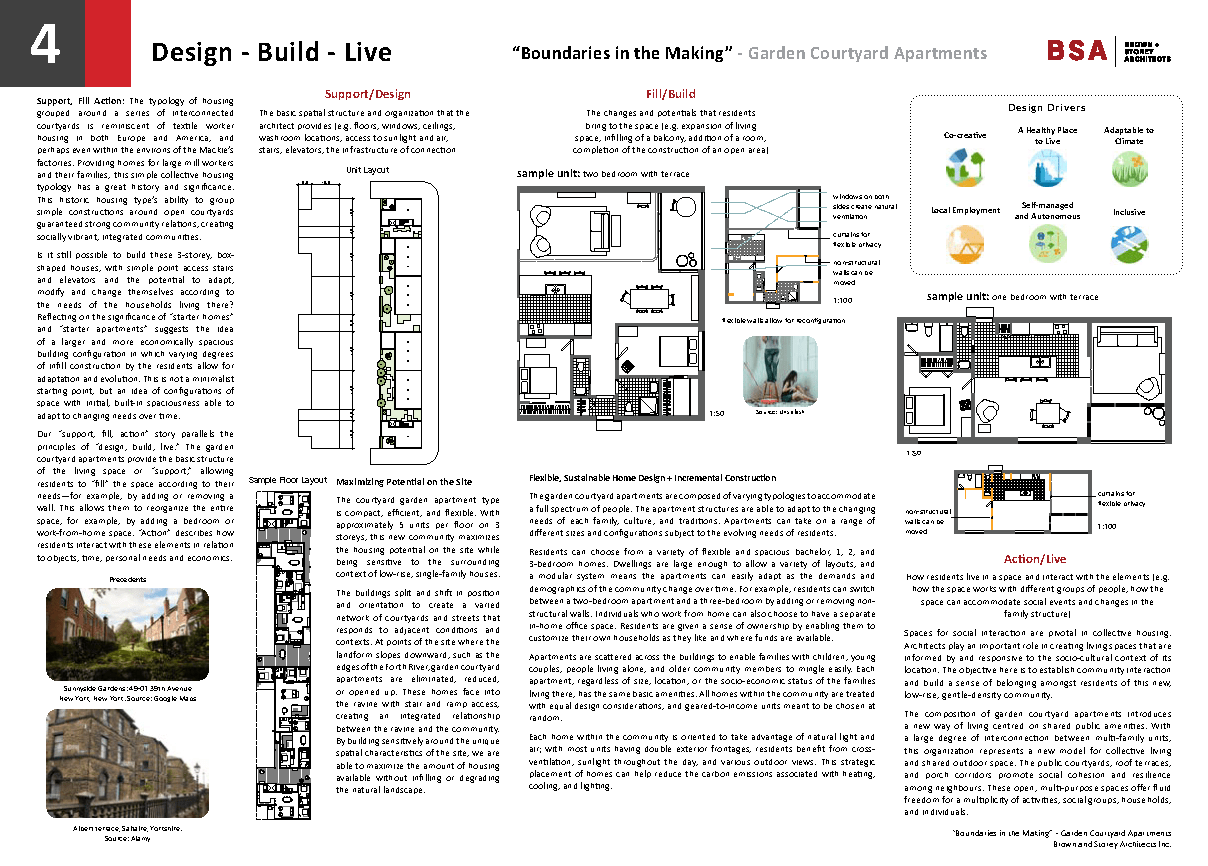

Courtyard Linkages and Connectivity

Street entrances, porch loggias, and bridges form a highly connected network across the garden courtyard apartments. The porch loggias have a number of interesting functions in the large system. Their initial task is to create two entry points to the courtyard that connect two adjacent streets. The households living there can control these entrance points—they can be left open during the day and closed to the public at night. Residents can also use sliding glass panels and curtains at the edge of the porch courtyards to modify the climactic conditions in this shared space.

As a system, porch loggias create connections between access points across numerous streets, common areas and allow shared access to multiple garden courtyard apartments. Courtyards access points become expressions of the households living there, taking on their own character and identity with different architectural treatments and degrees of transparency. These signature entryways can project into or retract from the street, entwine themselves with the streets. Residents walking by can catch glimpses into the inner courtyards and streets, visually enticing pedestrians to explore and discover the richness of daily life in their own neighbourhood.

Porch loggias also provide stair and elevator access to upper floor apartments as well as the roof terrace, with its gardens and solar voltaic collectors. On these upper levels, the porch loggias extend, becoming bridges that provide a safe linkage between apartments and their courtyards. The bridges create more degrees of access that further facilitate the sharing of amenities and resources between the garden courtyard apartments. They form a new horizontal network of terraces and landscapes above ground level and longer stretches of garden courtyard blocks can be consolidated as roof amenity space.

Sharing Households

“Luxury is the ability of inhabitants to live according to their own proper rhythms.” –Pier Vittorio Aureli, Less is Enough

Why don’t we facilitate larger spatial floor plates to allow apartments to facilitate a greater degree of self-organization? The challenge is not simply to make large apartments with excessive amenities, but to create a starting unit that is large enough to provide a more discursive array of spatial procedures. In contrast to the current market economy, in which developers incorporate as many units as possible into a building to maximize profits, a larger starting floor plan initiates a more intra-active relationship between the apartment and the resident, not confined to the pre-determined layouts typical of most apartments.

Dwellings in the garden courtyard apartments are not permanently defined as bachelor, one, two, or three bedroom apartments. Their scale allows for multiple of subdivisions of the space into further gradations of types and sizes of living spaces. This large, box-like starting point offers operational and spatial possibilities that are not available in a strict and minimal design, and allows units to adapt to the changing spatial and lifestyle needs of the family over time. The large spatial starting point for the garden courtyard apartments also allows the house form groupings around the courtyard to shift position relative to the adjacent courtyard, street and other elements.